We recently concluded the 2015-16 Board Leadership Series with a workshop titled “Turning Learning Into Action.” Near the end, I posed a question: “Can you effectively influence something that matters to you by focusing on changing something else?”

The answer is clearly YES.

We all live and work in systems, and the variables in a system are often related to each other in obvious ways. If you want more people attending your theatre, for example, you can lower the cost of tickets. If you want cleaner rivers, you can raise the capacity of sewage treatment plants in urban areas, or move the fences for grazing livestock in rural areas.

But what about when the connection is slightly less obvious? Maybe the level of ticket cost is less important than the level of ease of parking, or the level of outreach to local reading groups. And maybe what the clean river advocates should be focusing on is a legal designation that sets standards for “swimmable,” or a public campaign that features the history of the river and fosters pride in it.

This exercise raises the question of what other connections in the system we should be considering. Maybe theatre attendance correlates most closely with the closing times of neighborhood pubs. Maybe the health of the river is influenced over time most powerfully by the third grade curriculum.

The point is that our systems are complex, and it is a worthwhile exercise to pause and ask, “If I want to raise or lower levels of this, could I do it by raising or lowering levels of that?” The resulting thinking may focus our strategic efforts on new relationships and partnerships with those who have more influence over the various thats than we do. (This is one reason that so many conversations about fostering social benefits conclude, “We have to get into the schools!”)

For me, the connection we too often miss is the one between our external effectiveness as organizations and our internal habits as organizations, especially our habits in regard to how we spend time together. In my book, The Social Profit Handbook, I devote a chapter to the concept of mission time, that precious opportunity for ongoing learning and creative collaboration on important matters when there is not a sense of urgency.

We are inundated with urgent demands, though, so the non-urgent usually has to wait. And we can fall victim to our own unexamined assumptions about what it looks like to be working. We can start to think that reflection, particularly as a group, is something that happens when we are not working, as opposed to being at the heart of our work.

You can see how important mission time would be in order to pursue the idea of finding points of leverage. Mission time gives us the time and space and permission to examine the systems we are in and find those relationships between variables. It is the only chance we have to find the connections that are not staring us in the face.

And because we know we won’t have to wait until the next retreat to have mission time again, we can experiment. We can see what happens when we focus on other variables and examine the results.

So, along with other thoughts about turning learning into action, I left this year’s participants in the Dodge Board Leadership Series with this simple proposition: if you want to increase levels of (fill in any mission-based social good), just increase the number of minutes a week you spend with your colleagues in mission time.

David Grant is the author of The Social Profit Handbook, published by Chelsea Green.

David Grant is the author of The Social Profit Handbook, published by Chelsea Green.

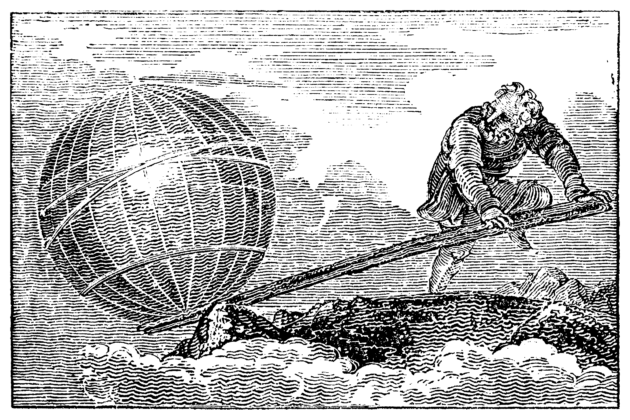

Photo at top courtesy Wikimedia Commons